Read This: The Elric Saga

Elric of Melniboné and his terrible sword Stormbringer made their first appearance in Michael Moorcock’s elaborate and fluid multiverse in 1961. Elric is rather a popular figure in popular culture, with the legendary albino prince showing up in comics and RPGs, songs, TV episodes, and tribute stories. Michael Moorcock’s own Elric tales are still being written, and are still being collected in various configurations with his older works. The character has always had a quality that seizes and inspires the imagination, and makes him a keystone of fantasy literature.

With so much Elric material to work with, I will only concern this overview with the original six novels of The Elric Saga as they were presented in 1984’s The Elric Saga Omnibus Part One (Elric of Melniboné, The Sailor on the Seas of Fate, The Weird of the White Wolf) and Part Two (The Vanishing Tower, The Bane of the Black Sword, Stormbringer). The omnibus editions are based on the canonical DAW editions of 1977, which gathered the existing stories into six volumes in roughly internal chronological order. The first book of the saga, 1972’s Elric of Melniboné, is a full novel in itself, while the last book, Stormbringer, actually collects several novellas first serialized in 1965.

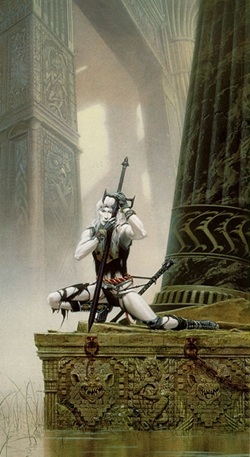

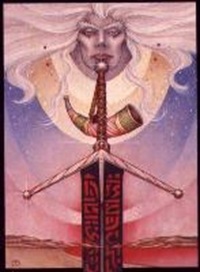

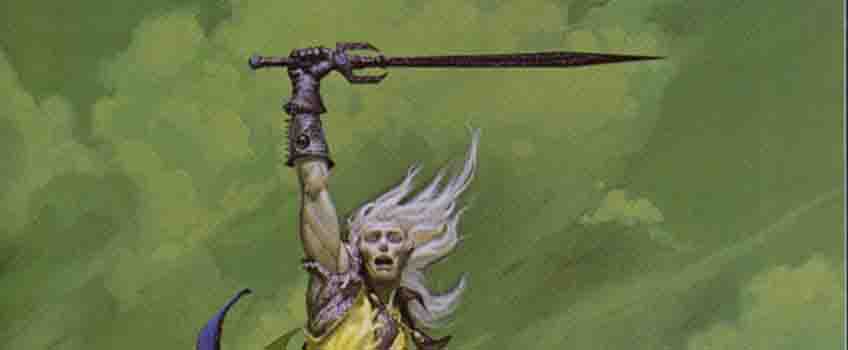

Although Elric of Melniboné first began adventuring in novellas over a decade earlier, in the first novel of the series Moorcock introduces Elric anew, and with much drama: “It is the colour of a bleached skull, his flesh; and the long hair which flows below his shoulders is milk-white. From the tapering, beautiful head stare two slanting eyes, crimson and moody, and from the loose sleeves of his yellow gown emerge two slender hands, also the colour of bone” (7, I). His melancholy and discontent are quickly established, as well as his initial main adversary. Within a few pages the stage is set for adventure, although we are made to wait for the appearance of Elric’s fabled sword: “’Stormbringer,’ he said. And then he felt afraid. It was suddenly as if he had been born again and that this runesword had been born with him. It was as if they had never been separate” (120, I).

Elric of Melniboné stands as one of the great antiheroes of epic fantasy, a cursed emperor who destroys his own kingdom and wanders the world on a fate-driven quest even he is unable to clearly define. From the first, Moorcock placed Elric in the midst of the unending struggle for Cosmic Balance between the Lords of Law and the Lords of Chaos, burdening him with the particular doom of being something more than mortal. Elric is also probably the most widely-known incarnation of the multidimensional Eternal Champion, whose mythology provides Moorcock a unifying theme for most of his work. But Elric is also in many ways the ultimate murder hobo, leaping from adventure to adventure as the opportunities present themselves, with his uneven allegiance to Chaos and his battle cry of, “Blood and souls for my lord Arioch!”

That devil-may-care, full-steam-ahead quality to the stories may explain why The Elric Saga has been an inspiration to uncounted other authors, including Gary Gygax as he developed Dungeons and Dragons. The settings and set-ups from the Elric novels all seem terribly familiar to anyone who has ever played D&D. For example, there is the classic location for parties to form–“Elric was looking for news and he knew that if he found it anywhere it would be in the taverns” (29, II), and the equally classic call to adventure, spoken by a magical damsel in distress–“Theleb K’aarna has joined forces with Prince Umbda, Lord of the Kelmain Hosts. Their plan is to conquer Lormyr and, ultimately, the entire Southern world!” (32, II). And with their clearly defined alignments of Law and Chaos, Moorcock’s gods were even incorporated into the early Dungeons and Dragons pantheon in the first edition of Dieties and Demigods.

Since Moorcock famously despises all things Tolkien, it is no shock that Elric is the antithesis of any of Tolkien’s most noble heroes. At heart, Elric is still a self-absorbed Melnibonéan, although he is slightly less selfish than the rest of his kind. Elric is motivated first and foremost by his own desires, despite his brooding over the damage they cause: “’My own instincts war against the traditions of my race.’ Elric drew a deep, melancholy breath. ‘I go where danger is because I think that an answer might lie there—some reason for all this tragedy and paradox. Yet I know I shall never find it’” (229, I). Although his fated role in keeping a cosmic balance is referenced often by his patron god, Lord Arioch, that purpose runs in the background of Elric’s own amorphous quest for meaning for the earlier part of the saga: ‘The Lords of Law and Chaos now govern our lives. But is there some being greater than them?” (315, I). However, the purpose fate has for Elric slowly overtakes his self-absorption and forces him slowly into a tragic, tainted heroism.

With Moorcock one of the founders of New Wave science fiction, The Elric Saga has the movement’s unmistakable flavour. The language is studiedly formal, a little stilted, and with much of the same style of descriptive repetition Lord Dunsanay used with great success. Moorcock creates a sly, dreamy effect that hints at humor without actually crossing the line. He is also wildly inventive, the imagery almost psychedelic with clouds and swirling colors and multidimensional awarenesses that anchor the stories in their swinging-sixties origins. But while the prose is often purple and melodramatic, it is never parody:

“Elric had been for skirting Old Hrolmar and riding on towards Tanelorn, where they had decided to go, but Moonglum had argued reasonably that they would need better horses and more food and equipment for the long ride across the Vilmirian and Ilmiorian plains to the edge of the Sighing Desert, where mysterious Tanelorn was situated. So Elric had at last agreed, though, after his encounter with Myshella and his witnessing the destruction of the Noose of Flesh, he had become weary and craved for the peace which Tanelorn offered.” (60, II)

While the writing is often playful and always clever, it is never smug. For all the fantastic characters and unlikely, whirlwind action, Moorcock takes his work seriously and crafts an artful and compelling epic that lures the reader into a world far deeper than first seems. Moorcock used his famous method for writing a book in three days for his Elric novels, and the fingerprints of it are all over it. Moorcock keeps the action constantly moving forward with a new event occurring every few pages. He drops references and mysteries in the novels that may or may not be answered but keep things rolling on. And he always has extraordinary images and outrageously named characters, objects, and places to throw into the action as the occasion arises–the Marsh of Mists, Orunlu the Keeper, the City of Screaming Statues, Rackhir the Red Archer, Dyvim Tvar, and other similar creations are littered throughout, building up a strange, vivid world to adventure in. But somehow the reliance on structure and plot devices results in something much greater than the sum of its many moving parts.

So, gaudy and action-driven with its own peculiar grandeur, The Elric Saga fits together in a surprisingly smooth clockwork of a tale. Moorcock may work with deep themes, but he doesn’t go for the studied gravitas of his nemesis, Tolkien, or the ponderous self-importance found in any number of fantasy sagas. Elric is serious, Elric is cursed, but Elric is also very, very interesting. It draws you in. It makes you care. If you haven’t read it from the source, yet, you need to go on that adventure.

E.A. Ruppert contributes book and media reviews for NerdGoblin.com. Thanks for checking this out. To keep up with the latest NerdGoblin developments, please like us on Facebook , follow us on Twitter, and sign up for the NerdGoblin Newsletter.

And as always, please share your thoughts and opinions in the comments section!