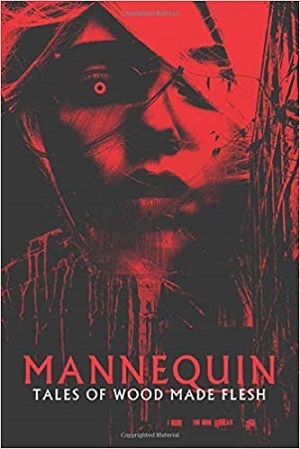

Read This: Mannequin: Tales of Wood Made Flesh

Mannequin: Tales of Wood Made Flesh, edited by Justin A. Burnett, is a well-crafted anthology built on the theme of disturbing simulacra. Dolls, statues, and mechanical men have been a staple of our storytelling since the days of myth. While there are plenty of memorable creations that are generally helpful and good, Mannequin steers clear of those types. There is not a Galatea or Pinnochio in the bunch, here, but there is a surprisingly broad range of other sorts. There are dolls of all different kinds, mannequins in various stages of intactness, wooden figures and mechanical puppets, toys and constructs and scarecrows.

None of them have our best interests in mind.

***

Following Christopher Slatsky’s thoughtful introduction are the sixteen disquieting variations on the theme:

Following Christopher Slatsky’s thoughtful introduction are the sixteen disquieting variations on the theme:

Ramsey Campbell’s “Cyril” is a disorienting stream-of-consciouness nightmare, with the narrative slipping between thoughts and dialogue. The doll here is an innocent compared to the greed of the main character.

Michael Wehunt’s “Balladyna” turns on a doll made to comfort a woman’s dying daughters. The descriptions of how the characters move through their house are vivid and unnerving.

Christine Morgan’s “Window Dressing” documents a woman’s loss of identity, and sanity, to a department store mannequin.

Richard Gavin’s “Crawlspace Oracle” is a gothically dark tale of possession. The doll, its keeper, and its victim inhabit a filthy space where prophecy is both power and chain.

Kristine Ong Muslim’s “The Incipient Eleanor” compactly chronicles the power struggle within an abusive and co-dependent relationship between a man and his mannequin.

Nicholas Day’s “The Part That Dies” puts a dark spin on life imitating art, with a surviving twin doing what he must to complete his brother’s final sculpture.

Austin James’ “Into the Fugue” follows a man as he reluctantly recovers the memory of his squalid upbringing, and his family’s reason for doll-making.

William Tea’s “Husks” presents a life-changing inheritance and a useful construct that would be a man. Earthy, gritty, and off-beat folk-horror that got under my skin.

Duane Pesice’s “Bobble” is short, tight, and delightfully bizarre. His choice of simulacra is sort of funny, right up until it becomes truly horrifying. One of my favorites in the collection.

S.L. Edwards’ “The Sickness of the Town” puts puppet governments and false idols into verse in a grimly political take on the anthology’s theme. The poem’s imagery made me think of Pink Floyd’s “Waiting for the Worms”, with its marching hammers and ugly facism.

Matthew M. Bartlett’s “Kuklalar” envisions a grotesque management culture with artificial supervisors, disgruntled employees, and a healthy dose of black magic. Solidly creepy.

S.E. Casey’s “The Night Shift” is another moody, evocative tale set in the workplace. Its organic corporate creations are needy, disturbing, and innocent. I can only wonder if they will stay that way.

Justin A. Burnett’s “She” unravels the connection between a detective, a serial killer, and the ghost of a doll trying to come back into existence.

Daulton Dickey’s “Allegory of Shadows and Bones” is a surreal, new-wave trek by a skeleton and his mannequin through a world that has ceased to be.

C.P. Dunphey’s “Dance of the Marionettes” is a dreamlike tale of gigantic hybrid beings and the weakness of the human condition, with a distance and mystery reminiscent of the Strugatskys’ work

Jon Padgett’s grim and mesmerizing closing piece, “To a Puppet, From a Dummy”, walks the fine line between personal memoir and fiction. I’m not sure how much to accept as real and how much as embellishment, but its effect is powerful.

***

The volume as a whole is full of unsettling creatures with wills and minds of their own. The stories, so effective individually, work together to produce a solid chill. There is a reason the uncanny valley exists. We will always be wary of things that are modeled after us or mimic us–whether we made them, or not.