Read This: Ian Fleming’s Goldfinger

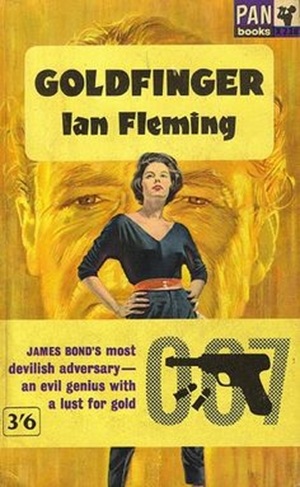

In all honesty, I had never read a James Bond novel before I stumbled over a copy of Goldfinger. With the impending release of Spectre, though, I decided the time was right to start. Goldfinger is Ian Fleming’s seventh entry in his Bond series, and by this point his government assassin is a well established character.

I was pleased to find that Goldfinger was surprisingly well written, smooth and very sharp, and with unexpected effort made to add emotional depth to a very cool operative.

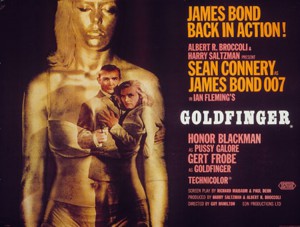

In this particular outing, James Bond goes up against Auric Goldfinger and his plot to steal all the gold in Fort Knox. Golf is played. Women are bedded. Fast cars are driven. Double entendres are made. Atomic weapons are brandished. Pretty standard fare for 007. A few plot changes were made for the screenplay, but if you’ve seen the movie (okay, pretty much any Bond movie), you know the basic story.

From Page to Screen and Back Again

I think by now we are all completely familiar with the big-screen versions of Bond. James Bond. From the swagger of Sean Connery, the smarminess of Roger Moore, the serviceable cool of Pierce Brosnan, and the suave brutality of Daniel Craig, Bond has been visualized for us for many, many years. For the most part, these Bonds display flawless self-assurance.

Which is why I didn’t expect the dark introspection of the character as Fleming wrote him. Goldfinger’s literary James Bond has an internal ambivilence that many of the big screen Bond’s ignore. While both books and films have reveled in plot twists and gagetry, Ian Fleming fleshed out his character in a way that only the last three films (and I am certain Spectre, too) have begun to seriously tap in to.

Fleming’s Bond is of course suave yet deeply carnal, eating and drinking well and richly, golfing and carousing and living the good life on his target’s dime. The familiar Walther PPK is there, and the references to his Astin Martin and beating Le Chiffre at the Casino Royale.

But there is much more to him, swimming just below the well-dressed surface.

A Thinking Man’s Operative

The opening pages of Goldfinger give us James Bond as a contemplative antihero, troubled by the killing his job entails. “He had never liked doing it and when he had to kill he did it as well as he knew how and forgot about it”(1). This Bond is stuck on the death of a low-level hit man on the fringes of a drug cartel.

What an extraordinary difference there was between a body full of person and a body that was empty!…something had gone out of him, out of the envelope of flesh and cheap clothes, and had left him an empty paper bag waiting for the dustcart. And the difference, the thing that had gone out of the stinking Mexican bandit, was greater than all Mexico (2).

In Fleming’s Goldfinger, Bond’s doubts only grow heavier as the novel unfolds. “What was wrong with him? Couldn’t he take it any more? Was he going soft, or was he only stale?”(47). When Goldfinger’s ‘secretary’ is murdered, Bond’s internal response is: “This death he would not be able to excuse as being part of his job. This death he would have to live with”(174). And when he plays along with the plan to rob Fort Knox even though it includes poisoning the town’s water supply, he cannot excuse his own decisions:

…whatever else Bond could now do, had sixty thousand people already died? Was there anything he could have done to prevent that?…Bond stared at his dark reflection in the window, listened to the sweet ting of the grade-crossing bells and the howl of the windhorn clearing their way, and shredded his nerves with doubts, questions, reproaches (246).

This is a novel full of casualties and collateral damage, and the way the dead are portrayed is part of Bond’s moral discomfort. Fleming at several points describes a dead body as being “empty,” and connects it to cast-off clothes. For example, as Bond approaches Fort Knox by train a dead man is drawn simply but clearly for us: “Over the levers something white was draped. It was a man’s shirt. Inside the shirt the body hung down, its head below the level of the window” (249). There is something very human about it, and very sad.

With a Few Blind Spots

Alas, that sharp sense of the existential, both Fleming’s and Bond’s, often goes astray. While it may have been considered racy when Goldfinger was published in 1959, the casual, desultory, and frequent sexism thrown about is jarring. The racism (which I will not detail here) is equally crude.

Even though Goldfinger’s female characters are written with intelligence and agency, they are still offhandedly dismissed throughout as “tails” and “tarts” and “little bitches.” Bond likes the challenge of strong women, because he knows he is always stronger—as when he takes control immediately upon meeting a woman for the first time: “Their eyes met and exchanged a flurry of masculine/feminine master/slave signals” (158). There is no way to avoid being dismissive given that dynamic.

Not even the infamous Pussy Galore is spared the blunt-force sexism freely slung about. Recruited as a criminal mastermind in her own right, her function is reduced to this: “Miss Galore will, I hope, provide the necessary contingent of nurses. It is to fill this minor but important role that she has been invited to this meeting” (223). And although she is written without any particular subtlety as a “Lesbian,” Miss Galore cannot resist the masculine charms of our James: “He said, ‘They told me you only liked women.’ She said, ‘I never met a man before’”(279). Because, let’s face it, James Bond is the only real man in the book.

Fleming does manage to provide an uncomfortable bit of depth for her, by giving her rape as a child as the reason she is a lesbian:

“I come from the South. You know the definition of a virgin down there? Well, it’s a girl who can run faster than her brother. In my case I couldn’t run as fast as my uncle. I was twelve. That’s not so good, James. You ought to be able to guess that” (279).

Unfortunately, this confession only reinforces the use of Pussy Galore’s sexuality as a plot device. It is yet another defense for James Bond to overcome.

Nobody’s Perfect

Despite the most severely dated aspects, it’s clear how Goldfinger and its companion volumes inspired such a long-running movie franchise. Well and cleanly written, Goldfinger turned out to be an exciting read, its plot and gimmicks familiar and surprising and delicious because of it. I’m confident that the rest of the book series, by Fleming and others, matches it in enthusiasm.

Having watched many of the films, I (and everyone else, really) certainly knew to expect the swaggering macho attitude found in the book. What came as a surprise in the novel version of Goldfinger was James Bond’s emotional discomfort and self-reflection tangled in with the war-stained, mid-century cultural attitudes toward women and minorities. The drinking, the gambling, the athleticism, the sexual prowess, even the blatant chauvinism—all these qualities belong to the James Bond we know and love. To those qualities we can now add accountability and a heavy conscience.

Without them, James Bond would be a stick figure.

With them, Ian Fleming gave us an icon.

E.A. Ruppert contributes book and media reviews for NerdGoblin.com. Thanks for checking this out. To keep up with the latest NerdGoblin developments, please like us on Facebook , follow us on Twitter, and sign up for the NerdGoblin Newsletter.

And as always, please share your thoughts and opinions in the comments section!