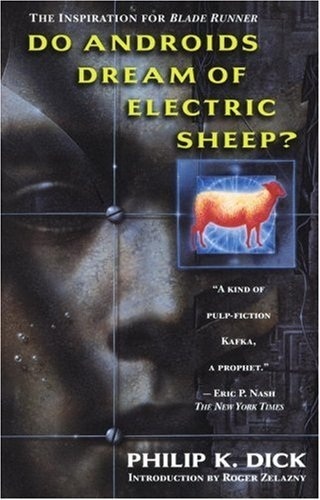

Read This: Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?

Once, he thought, I would have seen the stars. But now it’s only the dust; no one has seen a star in years, at least not from Earth –Philip K. Dick

Familiar to many as the film Blade Runner, Philip K. Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? is another classic of science fiction. Published in 1968, it dresses the traditional tropes of nuclear apocalypse, religion, and artificial intelligence in a brittle dystopic modernity. But its real subject is the eternal puzzle of our own humanity.

Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? describes one very long day for bounty hunter Rick Deckard, who is charged with “retiring” six androids who killed their human masters on Mars and escaped to Earth to try to live as human beings. The novel considers the issue of artificial intelligence obliquely—it is assumed that the androids of Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?’s dwindling Earth have their own desires and motivations, and are all but impossible to tell from natural humans without highly specialized empathy tests. In this world, it is not the androids’ ability to be self-aware that defines the difference, but their inability to feel for anyone but themselves. Or so the humans believe, in order to justify how androids are treated. Decker “had wondered… precisely why an android bounced helplessly about when confronted with an empathy-measuring test” (30). This question, and the assumptions it carries, twist beneath the plot in a way that never quite reaches an answer.

Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? is full of quiet desperation laced with dry humor. Every smile, every scrap of joy in this dusty world seems to be poisoned with sadness and disappointment. The apocalypse has come and gone, and the world still straggles on: “The legacy of World War Terminus had diminished in potency; those who could not survive the dust had passed into oblivion years ago, and the dust, weaker now and confronting the strong survivors, only deranged minds and genetic properties” (8).

Normal, Special, Other

Radiation-damaged humans are kept separated and dispossessed: “Once pegged as special, a citizen, even if accepting sterilization, dropped out of history. He ceased, in effect, to be part of mankind” (16). But even a special can instinctively grasp what the normal human characters often overlook: “You have to be with other people, he thought. In order to live at all” (204). On an Earth where the damaged are not considered truly human, it is the androids who can become the “other people,” who enable even a special man to fully live.

Human and android characters intersect frequently, both openly and in disguise. But they are all still dogged by loneliness, isolation, and the long slow drag of dehumanization. Decker’s wife explains that, “although I heard the emptiness intellectually, I didn’t feel it… then I realized how unhealthy it was, sensing the absence of life, not just in this building but everywhere, and not reacting—do you see? I guess you don’t. But that used to be considered a sign of mental illness; they called it ‘absence of appropriate affect.'” (5). The absence of appropriate affect is attributed to androids by their human masters, but the androids, enslaved on Mars, feel the emptiness, too: “‘nobody should have to live there. It wasn’t conceived for habitation, at least not within the last billion years. It’s so old. You feel it in the stones, the terrible old age'” (150). Distinctions are not so clear as the humans would have them.

Over the course of the novel Decker passes through stages of doubt, belief, and renewed doubt in android empathy. There are many descriptions of the range of emotions in the androids. “He did not like the idea of being stalked; he had seen the effect on androids. It brought about certain notable changes, even in them” (57); and “The androids,” she said,” are lonely, too” (150). But Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? leaves such references only partially explored by unreliable narrators, making them hard to evaluate. Even as the androids express needs and desires of their own, their reactions are presented as distinctly not human—at least not as humanity is defined by the human characters. When threatened with death, “The classic resignation. Mechanical, intellectual acceptance of that which a genuine organism—with two billion years of the pressure to live and evolve hagriding it—could never have reconciled itself to” (200); when using facts against faith, “They will have trouble understanding why nothing has changed” (214); when asked to react to a rare-to-vanishing living wasp, “‘I’d kill it.'” (49). But the differences described are vague and subjective. Decker’s inconsistency is understandable.

Empathy, Sympathy, Compassion

It is not only Decker. Many of the human characters are themselves adrift, searching for a way to connect. Post-war society has warped into something that enforces separations. Yet faith still endures. “At the black empathy box his wife crouched, her face rapt. He stood beside her for a time, his hand resting on her breast; he felt it rise and fall, the life in her, the activity. Iran did not notice him; the experience with Mercer had, as always, become complete” (177-8). Mercer, a Christ-figure, is the means through which believers experience community. But they do it in their own separate cells, using their own individual machines. They commune in solitude.

Empathy boxes are not the only mechanical attempt to connect with another being. With most animals dead, humanity has created artificial ones like the title’s electric sheep, robotic pets to fill the void left by extinction. But the nostalgia these imitations beasts produce is palpable:

“For a long time he stood gazing at the owl, who dozed on its perch. A thousand thoughts came to his mind, thoughts about the war, about the days when owls had fallen from the sky; he remembered how in his childhood it had been discovered that species upon species had become extinct and how the ‘papes had reported it each day–foxes one morning, badgers the next, until people had stopped reading the perpetual animal obits” (42)

Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? purposely muddies the distinctions between human and android, electric animal and living beast. It is never cleanly established what makes the androids truly different from humans. Aside from a short lifespan and a slower emotional response time to human-centric questions, they resemble their makers in all essential ways. What Decker believes about the androids is not always supported by what he observes, yet he clings to his version of the truth even as it seems less and less true. He has to. In a world where humans fill a void by embracing clockwork substitutes for real, living creatures, he cannot afford to embrace a substitute for himself.

E.A. Ruppert contributes book and media reviews for NerdGoblin.com. Thanks for checking this out. To keep up with the latest NerdGoblin developments, please like us on Facebook , follow us on Twitter and Pinterest, and sign up for the NerdGoblin Newsletter.

And as always, please share your thoughts and opinions in the comments section!