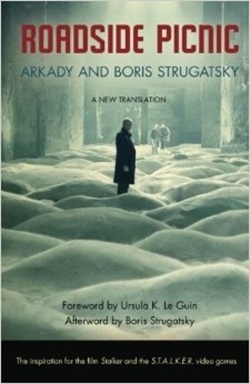

Read This: Roadside Picnic

Roadside Picnic by Arkady and Boris Strugatsky is a strange and affective science fiction novel—classic, understated, and far deeper than it initially seems. First published in Russia in 1972, its most recent translation (by Olena Bormashenko) was put out in 2012 with a foreword by Ursula K. LeGuin. The story is often prosaic, its events inexplicable, its conclusion tantalizingly inconclusive. The prose is direct, with little decoration. Yet it works. Memorably. Roadside Picnic forces the reader to consider humanity’s self-defined place in the cosmos, and in its own quiet way taps into the primal well of weird fiction by making that place very small, and very insignificant. But in the midst of that brush with nothingness it also presents us with a glimpse into the inner workings of human faith.

***

Roadside Picnic happens in a world where undescribed aliens landed, stayed for a while, and left again–all without making actual contact with humanity. The event is known as The Visit, the areas where they touched down are known as Zones, and the remnants the aliens left behind are deadly. “At night when you crawl by, you can see the glow inside, as if alcohol were burning in bluish tongues. That’s the hell slime radiating from the basement. But mostly it looks like an ordinary neighborhood, with ordinary houses, nothing special about it except that there are no people around” (21).

But men still go into the Zones, and most of them come back out intact. Whatever can be brought out is studied for possible use. The perverse wonder of the alien artifacts so many people die to acquire is that no one really has any idea what they are or how they work. There is speculation, much of it wrong, and occasional, accidentally found functionality. But no human understands this extraterrestrial stuff. It is all beyond them, as much as they want to believe that their scientific inquiry will lead them somewhere.

And still, the government studies it and the black market profits from it. Both sides believe, whether they realize it or not, that the aliens left these things behind for a reason—and if they just keep studying what they can drag out of the Zone, they will eventually discover something wonderful. Both sides of the law make plans of how to find their alien treasures, they develop strategies, they draw hopeful maps–but more than anything their survival and success in the Zone is only instinct and blind luck.

The Strugatsky brothers don’t try to disguise this perceptual fallacy lurking inside Roadside Picnic, and in fact explicitly state why the alien cast-offs remain inexplicable: “Xenology is an unnatural mixture of science fiction and formal logic. At its core is a flawed assumption—that an alien race would be psychologically human…biologists have already been burned attempting to apply human psychology to animals. Earth animals” (86). If we cannot ever hope to understand the aliens, we can never hope to understand what they create. It is as incomprehensible to us as an iphone is to an anteater.

***

In order to humanize the novel’s blunt philosophy, Roadside Picnic follows the life and career of one Redrick Schuhart. The plot is more of a slice of Red’s life than any traditional, hero’s journey-style narrative. When he is introduced at the age of 18, he works for the International Institute of Extraterrestrial Cultures by day, and as a stalker—a Zone scavenger–by night. His night work is illegal, and breathtakingly dangerous. He knows what’s at risk, but it still draws him in.

Redrick is an offbeat everyman. The character’s blend of cynicism and idealism, fatalism and vast hope, is realistic and attractive. Roadside Picnic follows him until he is 31, using his experiences as illustration. He may be a stalker, but he is an essentially decent person. He is a solid husband and father. He is a loyal friend. He is a disaffected employee, whichever side of the law he is working on. He has no grand plan. And yet, it is human nature to impose order on such planlessness—and where there is order, there is room for hope. And Red, believing in a stalkers’ legend and in his own personal goodness, still hopes for a higher meaning to come from what the aliens left behind.

***

And yet whether Redrick finds what he seeks remains open to multiple interpretations. In the end, Roadside Picnic is a disturbing and challenging novel. It’s observations about humanity’s ability to interact with the world, if accepted as true, are deeply uncomfortable to own. For the Strugatskys, the hope and faith they let their characters nurture is protection from a weirder truth–because when the Strugatskys look into the void at the heart of Roadside Picnic, nothing at all looks back.

E.A. Ruppert contributes book and media reviews for NerdGoblin.com. Thanks for checking this out. To keep up with the latest NerdGoblin developments, please like us on Facebook , follow us on Twitter, and sign up for the NerdGoblin Newsletter.

And as always, please share your thoughts and opinions in the comments section!