Read This: The Man in the High Castle

A year ago I reviewed the first season of the Amazon series The Man in the High Castle. Now, with the premiere of season two, I’d like to look at the source material. While I enjoyed Amazon’s version of Philip K. Dick’s Hugo-winning alternative history, the novel The Man in the High Castle is contemplative and tentative in ways that few TV series are equipped to handle. The two versions are complimentary, but not truly comparable.

***

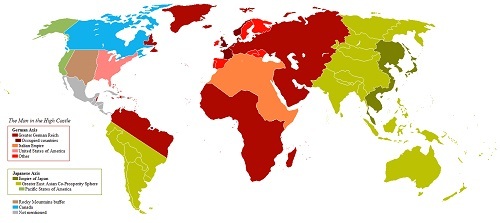

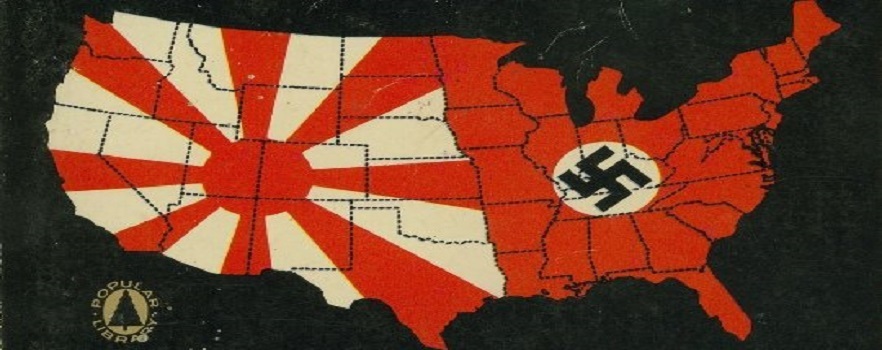

Philip K. Dick’s The Man in the High Castle was both published and set in 1962, and supposes a diametrically different outcome to World War II than we know. In this world the United States fell in 1947, and was carved up between imperial Japan and Nazi Germany. The Reich is a grasping power, and its relationship with Japan is strained and distrustful. Europe and Africa are ravaged by huge environmental and humanitarian deprivations. There is space travel, and nuclear weapons. There is also a haunting sense of instability. The world order is unsustainable.

***

Unlike its television interpretation, the novel The Man in the High Castle does not need bold action to move it along. Although many things do happen, they are small more often than dramatic. The novel relies largely on character development for its propulsion. Dick’s characters are more circumspect versions of their series alter-egos, and to varying degrees uncertain of their paths.

What is to me most striking about The Man In The High Castle is the finely-tuned tension running through it because of the characters’ uncertainties. The entire novel takes place in the through between sweeping political events, and is told from the points of view of people who are not aware that they can have any influence on the course of history–yet. That possible future influence fills the novel with potential energy as characters come to terms with the circumstances of their lives, and finally make the decisions to steer them rather than merely drift.

***

Also altered in translation are the importance of two books that form the thematic backbone of Dick’s original work.

The first book is a novel within a novel, titled The Grasshopper Lies Heavy—an alternate history to the alternate history it exists in. While Germany has reason to dislike the future envisioned in the subversive book, their banning of it does nothing to stop its popularity, or its influence on German citizens and subjects: “What upset him was this. This death of Adolf Hitler, the defeat and destruction of Hitler, the Partei, and Germany itself, as depicted in Abendsen’s book…it was all somehow grander, more in the old spirit than the actual world. The world of German hegemony” (133).

The second book is the philosophical guide The I Ching, which most of the characters use to decide the potential outcomes of their actions. It is an exercise in ambiguity and delicate moral complexity, of what may be and what might have been. Everything is open to interpretation, each throw of the sticks leads to a subtly different reading of the associated lines. Nothing is certain until action is taken, nothing is clear until it is in hindsight.

Under the influence of either or both of the two books, the characters decide their paths and reinvent both their places in this world and their ability to change them. Few of those changes are on a grand scale. Like so much else, they are incremental until the balance tips.

***

I recall a shrine in Hiroshima wherein a shinbone of some medieval saint could be examined. However, this is an artifact and that was a relic. This is alive in the now, whereas that merely remained. (185)

Unlike its serial adaptation, Philip K. Dick’s The Man In The High Castle is a story of transitions both personal and cultural. It is the story of characters coming to an understanding of where their lives have taken them so far, and what possibilities are open to them now. It is not merely an alternative version of the history we know. It is also an examination of how history is made, of the tiny components and the commonplace characters that are as much a part of its making as the men in power.

Lest we forget.

E.A. Ruppert contributes book and media reviews for NerdGoblin.com. Thanks for checking this out. To keep up with the latest NerdGoblin developments, please like us on Facebook and follow us on Twitter.

And as always, please share your thoughts and opinions in the comments section!