Ex Machina Thinks Before It Speaks

I would like to celebrate the recent home viewing release of the thoughtful Ex Machina as a counterpoint to the explosive summer blockbusters I have complained about in another post here, namely, “Mutants and Mosasaurus.” Ex Machina made its first appearance in the UK back in January, had its theatrical release in the US in April, and then made its way into a scattering of theaters over the following several months. If you missed it on the big screen, now is your chance to lower your adrenaline level and ramp up your philosophizing.

Spoilers will be kept to a minimum, here, because I prefer to dwell on the film’s themes and their presentation, rather than the plot. I think it is already common knowledge that Ex Machina has been offered up as intellectual science fiction. It has complex characters, low-key effects and minimal flash. The often-mentioned dance scene is as frenetic as it ever gets. By dwelling in its own details, Ex Machina gives its audience space to contemplate the evidence it presents for the hazards of artificial intelligence.

Ex Machina was written and directed by Alex Garland , author of the novels The Beach, The Tesseract, and The Coma, and of the screenplays 28 Days Later, Sunshine, and Never Let Me Go. In capsule, Ex Machina tells the story of Nathan, immensely successful creator of the Blue Book social network; Caleb, his low level employee; and Ava, Nathan’s latest attempt at creating truly self-aware artificial intelligence. Nathan selects Caleb for a variation on the Turing test to prove Ava’s abilities. Unexpected motivations emerge. Mind games ensue.

It is a beautiful, quiet, well-told little movie, filmed predominantly in a cool, rainy light. In its understated way Ex Machina does get under one’s skin.

The Players

Oscar Isaac (soon to be seen in Star Wars: Episode VII) is carnal as Nathan, fully inhabiting his physical form with a brutish, barbarian physicality that goes against the common stereotype of a programming genius. His Nathan is almost bestial in his appetites, greedy, virile, and aggressively in charge. Sweaty, barefoot, bearded, Nathan, beating a heavy bag in the outdoors gives a convincing an impression of man conquering nature.

In stark contrast, Domhnall Gleeson (also in the upcoming Episode VII) as Caleb seems rather uncomfortable in his own skin, not sure he is worthy of the honor bestowed on him. Lanky, pale, domesticated Caleb is awed by the force of personality that is Nathan and by the more subtle personality of the android Ava. Caleb’s insecurities are the tools Nathan and Ava both need to achieve their ends.

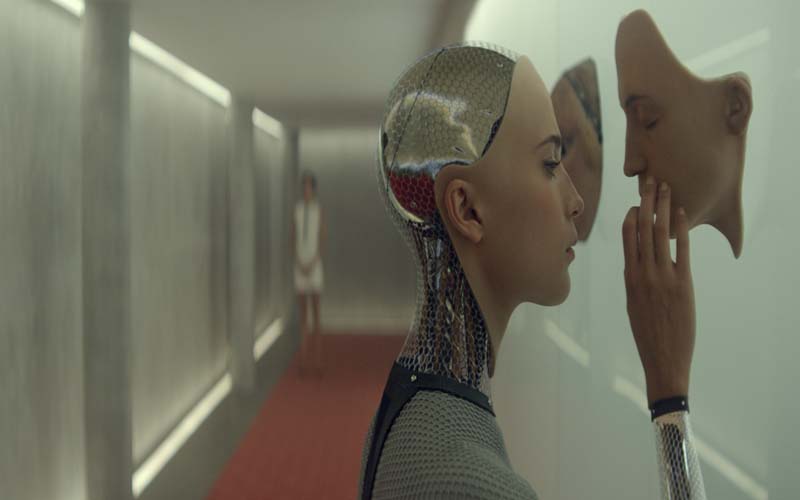

The sheer physicality of the actors contrasts starkly with the cool precision of the actresses playing the AIs. Both Ava (Alicia Vikander) and Kyoko (Sonoya Mizuno) are ethereal compared to their maker’s brooding mass and Caleb’s twitchy curiosity. Vikander and Mizuno are trained dancers, and it shows in the exquisite control and precision of their motions—they become convincing, wonderful machines. Ava is obviously inhuman, her plastic and metal showing, but her reasoning and desire transcend her appearance. Kyoko appears to be human, but she cannot speak. Her intellect and goals are revealed through less obvious means.

The Stage

Although Ex Machina’s overt story line revolves around the man-made world of coding, social networking, and artificial intelligence, Garland lets it play out against the backdrop of a primal environment. Nathan’s isolated house (in reality the Juvet Landscape Hotel in Norway) is a fantastic amalgam of modern design hewn into living rock, the organic fused to the construct. The visual interplay between the natural and the artificial reinforces the same interactions between the characters.

There are many such contrasts to be found in Ex Machina, with the majority of them surrounding Ava. There is the juxtaposition of Ava silhouetted in front of an enclosed garden, peeling off the layers of clothing that make her appear human and reverting back to her machinery. There is the faint whirring of her movements, and the lighted coils inside her that mimic the pattern of DNA. There is the warmer lighting in Ava’s cage, to give her warmer skin tones than the washed out complexions of the humans. Almost every scene carries this.

The Subtext

Wittgenstein’s convoluted philosophy plays a surprisingly large part in Ex Machina, underscoring the layers of misunderstanding that drive both the open and the hidden conflicts between Nathan, Caleb, Ava and Kyoko.

The reference to Wittgenstein’s Blue Book is dropped casually into the plot as the name of Nathan’s social media empire. The connection to the philosopher is mentioned as a curious detail and then ignored. It seems like a throw-away bit of intellectual dressing, but Wittgenstein’s philosophical construct of language and its limits goes to the heart of the movie. Much of his philosophy rests broadly on the idea that words are imperfect communication and inadequate in conveying real meaning. Words may circle close to what they are intended to express, but they will always be too blunt an instrument.

Ex Machina distracts us from its philosophy by directing its focus toward Ava’s ability to pass Nathan’s version of the Turing test. The Turing test relies on language, on conversation, to convince a human that a machine thinks (or appears to think) as a human does. Here is where the reference to Wittgenstein comes into play. An artificial intelligence may use the words a human mind has taught it, but the human can never be certain of the absolute meaning an artificial intelligence ascribes to those words, nor, consequently, an AI’s intent in using them.

This primary disconnect of meaning and intention aligns with the human tendency to anthropomorphize their creations and to impose their own biases upon the inhuman. We want to believe that other creatures think as we do, want what we want, and do so for the same reasons. These factors create a near-perfect opportunity for Nathan and Caleb to make terrible errors in judgement.

Caleb romanticizes his developing relationship with Ava and feels pity for Kyoko’s mistreatment, and Nathan perceives the apparent submissiveness of his creations as proof of his dominance. Neither is correct, and hidden within their mistakes is another aspect of Wittgenstein’s theories.

While Ex Machina’s attention is trained on Ava’s artificial intelligence, her ability to learn, converse, and coerce in a way that demonstrates human self-awareness, silent Kyoko has achieved her own self-aware personhood. Unable to speak, therefore exempt from the Turing test, Kyoko listens and observes, a recorder that has developed the ability to synthesize and understand. She is always present, listening as the humans discuss robot sexuality, and as Caleb discusses machine consciousness with Ava. She studies the Jackson Pollock painting after the men debate instinct and art. She watches for Caleb’s reaction when he discovers all the previous versions of android women Nathan stores in his bedroom. When she peels off her skin, we cannot tell for certain whether Caleb ever knew she was a construct.

Kyoko’s inability to speak releases her from the limitations of words. When she and Ava are finally able to interact, Ava also abandons spoken language. They have no problem communicating. Without the imprecision of words they share a flawless understanding—a reinforcement of Wittgenstein’s idea of language’s shortcomings. Their comprehension is perfect. Their artificial intelligence is real. They are aware. They have their own agenda.

And the two human men, whose lack of awareness of their own internal biases created a gap for the AIs to exploit, had only some small inkling of what the AIs wanted. Ava and Kyoko expressed their desires with the language they had been given, phrased in human terms but filtered through a machine’s intelligence. The humans heard what they were told, and thought they understood. Unfortunately, the meaning had changed in translation.

E.A. Ruppert contributes book and media reviews for NerdGoblin.com. Thanks for checking this out. To keep up with the latest NerdGoblin developments, please like us on Facebook , follow us on Twitter and Pinterest, and sign up for the NerdGoblin Newsletter.

And as always, please share your thoughts and opinions in the comments section!