Automata Is Less Than Meets the Eye

Automata, a bit of Spanish-Bulgarian science fiction from 2014, begins in familiar territory. A post-apocalyptic world. A monolithic city with the remains of humanity huddled inside. A vast, radioactive wasteland. And, naturally, sentient robots.

Automata, a bit of Spanish-Bulgarian science fiction from 2014, begins in familiar territory. A post-apocalyptic world. A monolithic city with the remains of humanity huddled inside. A vast, radioactive wasteland. And, naturally, sentient robots.

Many films have made these components work. But despite some talented actors, dramatic scenery, and the best of intentions, Automata does not manage to bring its vision fully to life. After a strong start, Automata falls into the trap of easy sentimentality and loses its way.

***

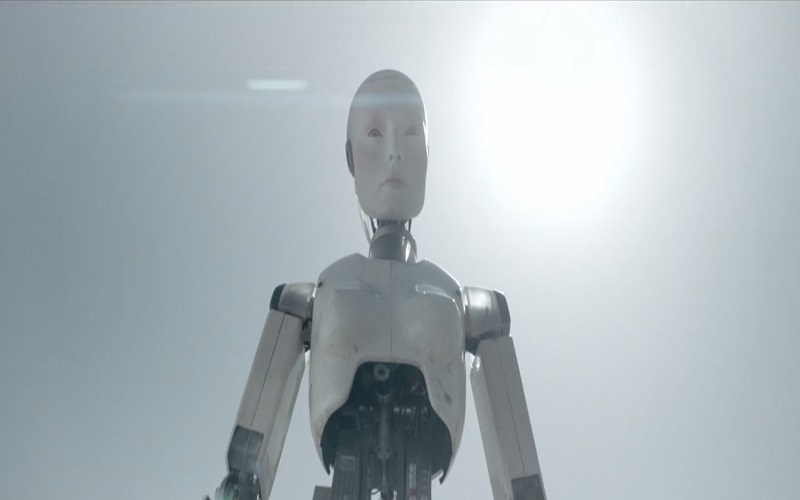

Automata is set in 2044, after the world has effectively ended. Humankind has been reduced to a only few million, living in fortress-like cities and served by ROC Corporation’s Pilgrim 7000s–humanoid robots designed for protection and manual labor. The robots operate under two immutable protocols: They cannot cause harm to any living thing, and they cannot repair or modify themselves or any other robot.

And then, one is discovered making its own modifications.

Insurance investigator Jacq Vaucan is assigned to find out who broke the robotic protocols and enabled the robot’s new ability. His search leads him deep into the remains of society’s underbelly, where he encounters dirty cops, dirtier corporate enforcers, child assassins, robotic sex slaves, black market “clocksmiths,” and, eventually, evolving, self-determining robots.

***

Visually, the cityscape is very much Blade Runner, right down to the rain, but without all the teeming people. The depopulation aspect spoke more to Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep, while the dull cubicle apartments hearkened back to Brazil.

Visually, the cityscape is very much Blade Runner, right down to the rain, but without all the teeming people. The depopulation aspect spoke more to Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep, while the dull cubicle apartments hearkened back to Brazil.

Yet despite its obvious derivativeness, Automata’s worldbuilding is pretty good. The aged machinery, the old cars, and the ancient tech all contribute to the weariness of the world. What is left is either industrial and dirty, with monolithic structures and walls, piles of garbage, or a bleak, dusty wasteland. The culture is adapted to the conditions without becoming outlandish. The slang seems unforced, with the bulky robots nicknamed “clunkers” and the radioactive desert called the Sandbox.

But Automata is less successful with building its characters.

***

The cast, overall, is overqualified and quite good, but many of the roles are flatly written or simply stock-types, too underdeveloped to be fully alive.

The cast, overall, is overqualified and quite good, but many of the roles are flatly written or simply stock-types, too underdeveloped to be fully alive.

Antonio Banderas stars as Jacq Vaucan, an insurance investigator sucked into the heart of a mystery. He is as brooding and mournful as ever, bringing a believable jadedness to his character. Dylan McDermott is threatening, cynical, and wasted as the corrupt cop, Wallace. Robert Forster plays Jacq’s supervisor Robert Bold believably as a worn-down but still compassionate company man. Birgitte Hjort Sørensen plays Jacq’s pregnant wife, Rachel, with convincing frustration and fear. Melanie Griffith, on the other hand, fails to convince as the robot-altering clocksmith, Doctor Dupré, with her baby voice and painfully slow delivery. She is more credible as the voice of the modified robot Cleo.

The remaining cast is filled out by Tim McInnerny, Andy Nyman, David Ryall, Andrew Tiernan, Christa Campbell, Bashar Rahal, and, surprisingly, Javier Bardem. The actors’ talents far outshine the scopes of their roles.

***

Automata’s plot also has problems. The film wants us to believe it is deep, but it is more stylish than substantive. The story builds steadily until Jacq leaves the city and enters the desert with a group of robots. From there, the plot loses its focus enough that at a reasonable 109 minutes, Automata felt padded. The long, sweeping scenes of desert and sky, the multiple flashbacks to the sea, the lingering close-ups of automata, all add length without contributing any needed development of the characters or story.

Automata’s plot also has problems. The film wants us to believe it is deep, but it is more stylish than substantive. The story builds steadily until Jacq leaves the city and enters the desert with a group of robots. From there, the plot loses its focus enough that at a reasonable 109 minutes, Automata felt padded. The long, sweeping scenes of desert and sky, the multiple flashbacks to the sea, the lingering close-ups of automata, all add length without contributing any needed development of the characters or story.

For all the visual grandeur, Automata is far less philosophically nuanced than Ex Machina or even Chappie. The robots are credited with incredible intelligence that far outstrips humanity’s. Unfortunately this intellect is expressed in soppy platitudes like, “Surviving is not relevant–living is,” and in creepy human-robot interactions that fail to highlight the intelligence of either species. Characters frequently toss out the idea that someone thought a robot was alive, but the implications of a living robot are addressed in a cursory, melodramatic way. The idea that the automata have become autonomous remains unexplored. The attempted religious overtones are not supported by the underlying themes, and the predictable action and sentimentality of the ending feels lazy rather than revelatory.

***

Automata is no classic, but it is not entirely a waste of time. While the plot is thin and the story stretched, the film is still quite beautiful. Banderas turns in one of his reliably lovely, melancholy performances, and the supporting cast is polished. In the end, I enjoyed it for what it is–an average film that wants to be more, but never does figure out how to get there.