Ghoul: Folklore, Fascists, and Fear

Ghoul, the new three-episode miniseries from Netflix, generates its chills with a blend of tried-and-true tropes borrowed from multiple well-known films and a dash of modern dystopia. While the derivative nature of the scares is a downside, Ghoul political dimension provides a different layer of darkness. Overall the film is a predictable but effectively-done horror movie, with an engaging cast and plenty of well-placed gore.

Ghoul, the new three-episode miniseries from Netflix, generates its chills with a blend of tried-and-true tropes borrowed from multiple well-known films and a dash of modern dystopia. While the derivative nature of the scares is a downside, Ghoul political dimension provides a different layer of darkness. Overall the film is a predictable but effectively-done horror movie, with an engaging cast and plenty of well-placed gore.

“False sense of patriotism that seems to be spreading through the country.”

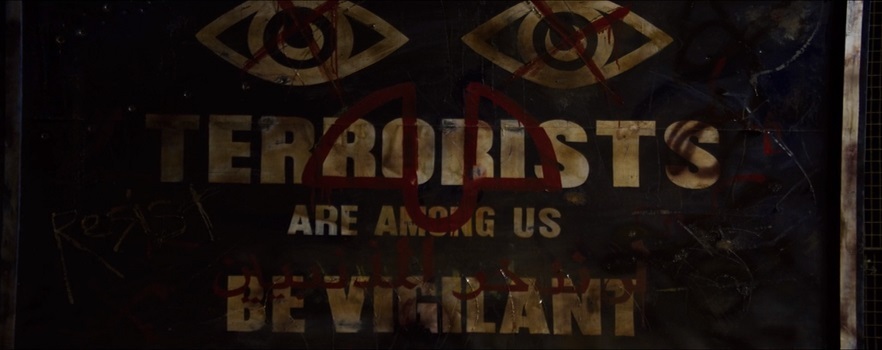

Ghoul unfolds in a near-future India that has fallen into fascism, with secret prisons, brutal re-education, enforced political orthodoxy, and questions of how religion impacts patriotism.

The story centers on Nida, a young Muslim woman training to be a government interrogator. Her father refuses to toe the political line. She turns him in, choosing patriotism over faith and family. Soon after, she finds herself assigned to a secret interrogation center where the arrival of a dangerous new prisoner sends the whole command structure spiralling into chaos and death.

Nida is played with great sincerity by Radhika Apte. S. M. Zaheer is her stubborn, seditious father. Manav Kaul is sympathetic as the drunk and troubled Colonel Sunil Dacunha, the man in charge of the prison. Ratnabali Bhattacharjee’s Lieutenant Laxmi Das is convincingly twisted as Dacunha’s duplicitous second in command. And Mahesh Balraj brings a creepy stoicism to the monstrous terrorist Ali Saeed.

“The ghoul shows as the reflection of our guilt.”

Anyone who watches horror movies will recognize plenty of familiar tropes. But an old story told well is still worth watching. And I think Ghoul tells its old story well.

Anyone who watches horror movies will recognize plenty of familiar tropes. But an old story told well is still worth watching. And I think Ghoul tells its old story well.

The film is atmospheric, with a haunted house vibe that uses the desperation of The Blair Witch Project, the industrial oppression of Alien, and the paranoia of The Thing among its many inspirations.

Visually, the decrepit prison setting where Ghoul happens is also very familiar. Built as a bunker against nuclear attack, the site is of course not in any official records. But the film adds a few extra details that ramp up the totalitarian mood. Black-painted windows disguise night and day. Exterior shots of brutalist architecture reinforce the heavy-handed repression at work in this society. The incessant rainfall outside the massive buildings produces its own claustrophobia. Everything is bleak, dull, and colorless, except for the stunning splashes of red when the monster is revealed.

And the reveal comes quickly. Unlike the graveyard-dwelling, corpse-eating demon of pre-Islamic folklore, the ghoul in Ghoul is a demon of vengeance summoned in retribution. It takes the form of the last person whose flesh it ate, but here it teases out confessions of guilt before it attacks.

“Finish the task, reveal their guilt, eat their flesh”

Ghoul is written and directed by Patrick Graham with inconsistent levels of subtlety. The dialogue is at times very formal and stagey, with power struggles and plot turns telegraphed far in advance. The plotting is slow, grim, and pointed. Terrorism and political orthodoxy are major themes, as is suspicion of any display of faith. If there was any doubt about the point Graham was aiming at, the pile of pulled gold teeth and a crematorium should remove it. The three episodes could have easily been trimmed to two hours. The padding betrays its origins as an intended feature film.

Ghoul is written and directed by Patrick Graham with inconsistent levels of subtlety. The dialogue is at times very formal and stagey, with power struggles and plot turns telegraphed far in advance. The plotting is slow, grim, and pointed. Terrorism and political orthodoxy are major themes, as is suspicion of any display of faith. If there was any doubt about the point Graham was aiming at, the pile of pulled gold teeth and a crematorium should remove it. The three episodes could have easily been trimmed to two hours. The padding betrays its origins as an intended feature film.

It is still creepy as hell. The slowness, the obvious references, even the predictability of events do not diminish the skill of the cast and the strength and style of the storytelling. Ghoul may not break any new ground, but it is a solid reminder of why stories like it continues to be retold.