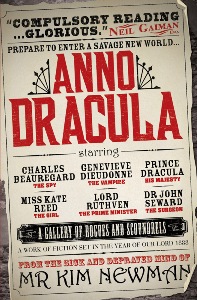

Read This: Anno Dracula

There is something to be said for steam-punky Victorian supernatural dramas. With Penny Dreadful’s eclectic cast of characters churning gorily along toward the end of their second season and Fox preparing to take another stab at The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, we should really take a look back at a book whose style, substance, and methodology reminds me very much of these two other tales.

There is something to be said for steam-punky Victorian supernatural dramas. With Penny Dreadful’s eclectic cast of characters churning gorily along toward the end of their second season and Fox preparing to take another stab at The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, we should really take a look back at a book whose style, substance, and methodology reminds me very much of these two other tales.

Kim Newman’s 1992 alternate history/crime drama/horror opus Anno Dracula is the first of a series of wonderfully tangled novels populated by characters he pulls from pretty much everywhere—vampire fiction, pulp adventure stories, literature, history, television and films. Newman’s devious mind creates a century-spanning pop-culture wonderland in the process of constructing a fully-realized alternate world history where Dracula is not only real, but where he has become the de facto ruler of the British Empire.

This reimagined world blooms into vivid unlife when Dracula defeats Van Helsing et al., and insinuates himself into the upper levels of British society. Newman’s Prince of Darkness vampirizes and marries Queen Victoria and sets himself up in Buckingham Palace as the Prince Consort, filling high government positions with vampires of his own making and steadily gaining control of Great Britain, her colonies, and her allies. The ranks of the powerful are full of (literal) bloodsuckers. The more things change, eh?

Of course, many of the fashionable (and power-hungry) set want to be part of this new order and seek out the vampire life for themselves. Trendy rather than cutting edge, “they were sleeping in earth-lined coffins in Mayfair, and hunting in packs in Pall Mall. This season, the correct form of address for an archbishop was hardly of major concern to anyone.” (10).

And also of course, the fashions adopted by the upper crust trickle down. Newman’s story begins in a new Old World where a growing number of the middle and lower class on an international scale have also chosen to become vampires, and follow their father-in-darkness where he roams: “The Prince Consort’s London, from Buckingham Palace to Buck’s Row, is the sinkhole of Europe, clogged with the ejecta of a double-dozen principalities” (5). Even vampirism can’t solve immigration issues.

Such huge, rapid social changes take time to smooth out; but that time has not yet passed when a series of bloody and politically inconvenient murders begin in the bowels of London.

Against his unsettled backdrop, Newman throws in Jack the Ripper to prey on vampire prostitutes (yes, prostitutes, because poor vampires still need to support themselves somehow). The Ripper’s continued attacks strain the fragile social and political balance that exists between the rich, the poor, the quick and the dead. London’s detectives, both human and vampire, official and incognito, must work together to solve the mystery of the Ripper’s identity and stop his brutal rampage.

The hub for the investigation is the Diogenes Club, a gentleman’s club pilfered from Arthur Conan Doyle’s work and repurposed by Newman as a nexus for the Crown’s secret agents, adventurers, and other men of influence and action. It is a gathering place for the loyal, yet fundamentally pragmatic, brokers of power. Most of them are even still alive.

One of the still-warm members of this secret government hangout is our hero Charles Beauregard, a human adventurer who is charged (at least officially) with finding and stopping the Ripper. He is aided by the equally heroic Geneviève Dieudonnè, a four and a half centuries-old French vampire who appears still to be a sixteen year old girl. These two are representative of Newman’s few original characters–they are resonant, well-developed personalities that bind the whole blood-soaked, name-dropping, convoluted confection together and make it float.

Newman’s prose is rich and dark, lit with flashes of humor. He isn’t writing solely to move the plot along. He enjoys this. Immensely. When Newman describes the desecrated throne room, you can smell the congealing blood:

“Ill-lit by broken chandeliers, the throne room was an infernal sea of people and animals, its once-fine walls torn and stained. Dirtied and abused paintings hung at strange angles or were piled loose behind furniture. Laughing, whimpering, grunting, whining, screaming creatures congregated on divans and carpets. An almost naked Carpathian wrestled a giant ape, their feet scrabbling and slipping on a marble floor thick with discharges” (341).

You wouldn’t think that “discharges” could be such a dirty word.

Newman makes it very clear that the Prince Consort is an unmitigated monster, with even his descendants tainted by the “grave-mould in his bloodline” (49). Newman dwells little on Victoria herself, but manages to disassemble her iconic persona with a few choice images: “The Queen knelt by the throne, a spiked collar around her neck, a massive chain leading from it to a loose bracelet upon Dracula’s wrist. She was in her shift and stockings, brown hair loose, blood on her face” (343).

To people his novel, Newman mined deeply into Victorian adventure and vampire fiction as well as history, modern film and television. Some of the many personages Newman works into his story-line are Bram Stoker and his wife, Stoker’s brides of Dracula, John Seward, Mina Harker, Kate Reed, Dracula himself, Elizabeth Bathory, Billy the Kid, Kurt Barlow from Stephen King’s ‘Salem’s Lot, Barnabas Collins from TV’s Dark Shadows, Edward VII, Beatrice Potter, Kipling’s Gunga Din, George Bernard Shaw, Sherlock and Mycroft Holmes, Professor Moriarity, Orson Welles, Dr. Jekyll (and Mr. Hyde), Dr. Moreau, Oscar Wilde, and Count Orlok from the legally questionable Nosferatu. There is a lot going on. It is exhausting to even partially catalogue them, and fun to spot them. Newman makes good use of every one.

And because that much research and synthesis should not be wasted, Newman follows up on a few of his long-lived mortals and surviving undead with an additional three novels set in his alternate reality–The Bloody Red Baron, Dracula Cha Cha Cha (or, Judgment of Tears), and Johnny Alucard—and with a smattering of short stories. They are all continuing cultural amalgams that check in at various points during the twentieth century, carrying us at last into and straight through the disco era.

If you haven’t already read any Kim Newman, I strongly encourage it. Especially if you enjoy your prose bloody and your cultural references flying fast and thick, pick this one up. You may not recognize the all the scenery, but you will certainly enjoy the ride.

To keep up with the latest NerdGoblin developments, please like us on Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/NerdGoblin and follow us on Twitter: https://twitter.com/thenerdgoblin.

And as always, please share your thoughts and opinions in the comments section!