Children of Men: Two Sides to the Story

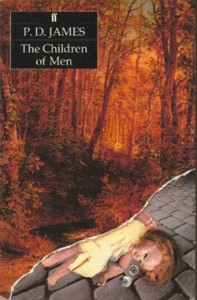

When it comes to adaptations, I am normally a stickler for the purity of the source material (I’m looking at you, Peter Jackson). I realize there will always be exceptions like The Princess Bride, when a book’s narrative structure makes it difficult to film but it still has a viable story to be told, or adaptations which tell the core story in a way that is distinctly their own—inspired, rather than adapted, different yet equal—like Blade Runner and Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep. And last there are those adaptations where the movie is far better than the book ever was, tapping into the story’s potential in a way the words on the page have failed to do. That, I think, is the case with P.D. James’s The Children of Men and the film made of it.

Since I thought the movie version of P.D. James’s foray into bleak speculative fiction was excellent, I figured I would check out the source novel. I was intrigued by the idea of James writing dystopian fiction, since she was well known for her literary mysteries and not for her near-future world’s ends. But dystopia is not something strictly relegated to multivolume science fiction epics. Dystopia is a concept that rears its head among the literary set with some regularity. Think 1984. Think Brave New World. James is respected. What could go wrong?

A lot, actually. While the novel was undeniably well-written, I expected much more than I got. The Children of Men is a fairly dry story about not particularly nice middle-aged to elderly people, many of whom are Oxford University professors, all of whom are jockeying (openly or in secret) for control in a dying world. It is a slow-moving work, spending more than half its pages in setting the stage before anything actually happens. Told alternately as first-person diary entries and third-person narrative, the plotting is solid and polite and the characters’ evolutions not truly believable.

The end of the world has already happened when the story begins, and the novel unfolds in the long, slow decline that comes in its wake. Human fertility petered out twenty five years before. Society is crumbling at the edges, but the aging population can still go about a fairly normal routine that becomes more limited as the days pass. Their suicide is encouraged by the newly-totalitarian government as a means to preserve resources as long as possible.

The last-born generation, the Omegas, have become dangerous and uncivilized as their elders come to grips with the end of the world. James dwells on the collapse of society, and the re-embrace of the brutal pagan past: “that even the frozen sperm stored for experiment and artificial insemination had lost its potency was a peculiar horror casting over Omega the pall of superstitious awe, of witchcraft, of divine intervention. The old gods reappeared, terrible in their power” (8). She imagines a different kind of lost generation, one that has gone feral because they no longer represent hope for the future.

But James’s characters seem brittle and not especially likeable. Theo, the keeper of the diary, is a middle-aged professor of history whose conversion to the rebel cause is less than convincing. His falling in love with the blank slate of Julian, the first pregnant woman in a generation, seems built on nothing in particular, as does her mutual attachment to him. Theo’s main value seems to lie in his family connection to the head of the ruling council, a man so entrenched in his power that he can throw out grim philosophies like, “We plan for the sake of planning, pretending that man has a future” (102). There is little warmth to be found in the novel, and even with an eventual birth James leaves her readers with very little to hope for. But she does leave us with an intriguingly sharp observation about the lure of power.

And yet something more passionate came from it.

Despite its emotionally chilly source, Children of Men was a well-received 2006 movie that took a large number of action-oriented liberties with the plot, transforming The Children of Men from a mannered, upper-class dystopian novel into a deeply touching film about the fight to preserve human worth in the face of societal collapse, whatever the personal cost. The film shows the effect of the gradual loss of hope much more vividly than the book does, through younger eyes and by more violent means. But it also shows that while hope exists, there will always be people willing to sacrifice themselves to make it bloom. Resilience, kindness, and an unquenchable willingness to help underlie the grim, dehumanizing world of this Children of Men.

The story begins with the same triggering event as the novel. But it also begins in a crowded London with the populace soaked in government-sponsored nationalism and fear of illegal immigrants. The characters have considerably more emotional depth than in the book, and the actors have a lot to do with the humanity of the tale. Clive Owen especially brings a nonacademic fullness to Theo that is lacking on the page. And the script sees fit to give them all more realistic motives, with some tie to either current or past radicalism and a deep well of sympathy to draw from.

In this version, the British government’s Homeland Security rounds up its immigrants for transport to a city converted to a brutal internment camp. Everyone is armed and willing to kill, with rebel groups fighting a guerrilla war against the government repression. Julian is reimagined as a radical involved with a terrorist gang to protect a young, miraculously pregnant immigrant woman from government interference. Trading on old relationships, she draws Theo into their plot. Theo’s ties to power, so vital in the book, are no longer central—they exist, but he becomes truly valuable because of his own qualities and his commitment to saving the pregnant woman.

While I normally enjoy a film less than its inspiration, this is a case where the original material left me cold. I found The Children of Men to be beautifully written but so full of unpleasant people that I can’t honestly say I cared what happened to them. The movie, though…if you are looking for an adult dystopia, Children of Men will serve well. Despite the terrible imagery that fills it, this Children of Men still ends with fragile optimism. Same characters as the book has. Same events. In some cases scenes transcribed verbatim. But by shifting the perspective from the machinations of power to the power of hope, the effect on film is something wholly different than the original material can produce.

E.A. Ruppert contributes book and media reviews for NerdGoblin.com. Thanks for checking this out. To keep up with the latest NerdGoblin developments, please like us on Facebook , follow us on Twitter, and sign up for the NerdGoblin Newsletter.

And as always, please share your thoughts and opinions in the comments section!

The entire point James is trying to make in her novel is that the characters aren’t particularly likeable; they seem boring and dry because in their situation they can do no more than what they were doing before the year Omega. She doesn’t romanticise the end of the world like a lot of science fiction dystopias. She imagines a world which is probably a lot closer to the truth than traditional dystopia would have us believe. In the world of The Children of Men, humanity is coming to a slow but definitive close; we aren’t wasting away from nuclear waste or other man made causes, it is just the simple erasure of biological processes. The most remarkable thing about James’ novel is that it is unremarkable in plot and characters. She crafts them in a way that reflects the people and attitudes of the time and they are so close to us in real life that you almost forget that humanity is dying out from a faceless cause that is never identified. She has incorporated techniques from her mystery and crime writing; she leaves us with a puzzle to solve ourselves, the cause of the mass infertility. Many in the book hypothesise over the reason but they never draw a definite conclusion. Her style of writing and craft in this novel are exemplary and the fact that you almost completely disregard the incredible details that went into her work when comparing it to the film adaptation is naive. She selects Theo as her protagonist as a move away from the traditional romantic, dashing and brave protagonists of most dystopias; she normalizes the end of the world in a way no other author has. The film eradicates her attempt to style a different type of dystopia and inputs back into it the traditional tropes of apocalyptic and dystopian works.

I am glad I’m not the only one who found Children of Men to be the great white unicorn where the film is by far better than the book. I think you do justice to both works and found your analysis and judgement of James’ writing to be more than generous and fair. I’ve always found PD James writing to be technically good, but totally lifeless. I was amazed at how Cuaron took what was, for me, a very good thought piece but with characters that you mostly wished would just shut up, and turned it into an almost entirely visual story with characters that felt truly tragic and real and who you could dislike and admire all at once. James idea for this story is very good, but Cuaron takes that rather cold novel and crafts it into something truly alive and haunting; familiar and futuristic all at once. I am more of a reader than a watcher, so it’s very hard for me to find films I want to re-watch over rereading a book. I have watched C of M many times now and often recommend it. I’ve never bothered to reread the book. This is the only film adaptation I can say that for!