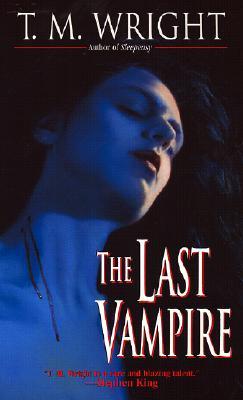

Read This: The Last Vampire

The horror author T. M. Wright passed away on Halloween. By pure coincidence I had just reread his 1991 novel The Last Vampire when the news of his death came down. Wright was a skilled storyteller with an often surprising imagination and a deep sense of life’s essential melancholy, and he was quite prolific over the course of his career. While his style can be an acquired taste, I admire his way of exploring the dark and I think his work should be remembered. So please forgive any poignancy in what was supposed to be a simple review.

Although I had encountered his work when I was a kid, I didn’t recognize Wright’s name when I found a copy of The Last Vampire in a vacation rental some ten years back. I started it as a way to read myself to sleep, but the premise and the storytelling were so… different, so haunting… that I took the old paperback with me when I left.

The Last Vampire has a meandering, nonlinear narrative structure and gives a fine example of an unreliable narrator in the title character. Wright’s style is dreamlike, suffused with loss, and sadness, and nostalgia, and an ability to twist and recombine genre tropes into unexpected constructs. His prose moves quickly, and the story slips by even as it circles back on itself and retells certain resonant fragments.

The Last Vampire takes place after a nuclear apocalypse has wiped out most of humanity. Wright begins with a frame story that is never completed, and is then, after a short, unconnected section about a midnight vampire rodeo, told entirely in the first person by the last vampire himself, Elmer Land. The frame occurs about fifty years post-apocalypse, while the bulk of the novel happens shortly after the destruction. Wright repeats passages to mimic a slipping memory as Land recounts his existence as both human and vampire. Regrets creep in during the telling, and exhaustion. “I persist, even now. Persist. Persist. Resist. Cannot go away. Leave nothing, take nothing, break hearts and bones, hearts and bones…” (62). There is a mood to The Last Vampire that echoes the mood in Tanith Lee’s short story “Nunc Dimittis”—a pervasive sense of loneliness and of too much time spent merely existing.

Elmer first appears as a disembodied spirit reaching out, not so much for contact as for proof that he had been, once: “One moment we’re a living person, we have the needs of a living person, the next moment we’re an obscenity, then, moments later, we’re an apparition. I believe at this moment in my existence, I’m an apparition” (22).

And at the end of the world, what remains of the last vampire is also the last connection to the common dead:

“…they whisper to me that they never ever thought it was going to be like this, that they had expected something a bit more final, or a bit more ethereal. But they wait inside themselves, instead, and watch their bodies come apart, and they feel the awful pain that they were so certain death was going to bring an end to” (64).

Being a revenant himself, Elmer is aware of the world’s lingering ghosts. He cannot speak to them because of his own limits, but he can hear their complaints and affirm the dimming memory of their lives. It is the same affirmation he seeks for himself.

A defining quality of vampirism in The Last Vampire is the lack of one’s own senses. Elmer may hear the thoughts of the dead, but he relies on his similar ability to “read” the living to be able to see and hear the world around him. Much of it still remains beyond his experience, and he knows what he misses: “I need to talk about my first kill. Call it nostalgia, I suppose. My memory of it stirs something sweet in me. Bitter-sweet. I could never taste blood, though I’ve always wanted to”(225-6).

While his vampire is still a bloodthirsty monster, Wright infuses the character with a layered sense of his own identity. Elmer Land describes his state as, “…like a termite eating someone’s house up. I can’t be reasoned with, I can only be exterminated, and that is so terribly difficult” (137-8). But he still defines himself as a different thing than the vampire who made him. She was “…the archetypal vampire…a wide-eyed, quivering, and insatiable mass of fears and compulsions which, because of its own needs, eventually dooms itself”(199). Elmer was never superstitious in life; and in death escaped the trap of becoming what the legends said he should be. But the bloodlust was inescapable: “I knew so well about compulsion. Here I am, inside this creature, this old corpse that still tries to animate itself, and I want to cry my eyes out. I thank God I cannot live forever. I thank God that the house has fallen down around me and there is no more work for me to do” (262). Elmer’s remaining consciousness is still self-aware, and with that comes regrets about what his life and death have made of him. There are elements of self-loathing, but they are secondary to the great weariness of a creature that has far outlived his own wants.

In The Last Vampire, T.M. Wright takes his readers to the world’s end to endure compulsion, nostalgia, loss, and desire. These are themes that Wright has explored in other works as well. He is comfortable with them, and adept at making his reader feel what is gone. And since I am not ready to let him go just yet, my next post will look at how he interpreted those themes through a living protagonist in the first novel of his that I read—A Manhattan Ghost Story.

E.A. Ruppert contributes book and media reviews for NerdGoblin.com. Thanks for checking this out. To keep up with the latest NerdGoblin developments, please like us on Facebook , follow us on Twitter, and sign up for the NerdGoblin Newsletter.

And as always, please share your thoughts and opinions in the comments section!