Read This: Do Zombies Dream of Undead Sheep?

As summer draws to an end, our fancies may once more turn to the shambling, hungry undead. If your interest in all things zombie extends beyond “It’s a virus!” or “It’s a fungus!” to what could actually cause typical zombie behaviors, Do Zombies Dream of Undead Sheep? A Neuroscientific View of the Zombie Brain by Timothy Verstynen and Bradley Voytek might be just the book for you.

Do Zombies Dream of Undead Sheep? is a much more genteel read than the title suggests. Honestly, I was expecting something more gratuitously zombie. You know, actual zombie autopsies, or necropsies, or experimentation—some such horror-movie splatter. Fear of the Walking Dead isn’t going to tell us how these creatures work. We need to know, if we are going to make it!

But this is not, after all, the nuts-and-bolts toolkit of Max Brooks’s The Zombie Survival Guide. There is no hard-core practical survival advice to be had here, despite the final chapter that purports to offer some based on the concluded causes of zombification.

Instead, this book serves up a simplified but thorough overview of brain structure and function illustrated with a mix of real-life case studies, silly, zombified artwork, and examples from a variety of zombie movies. Both Timothy Verstynen and Bradley Voytek are neuroscientists, university professors, and zombie buffs, which perhaps explains their desire to share their combined passions for neural function and the shambling undead with a lay population.

And they know that their combined passions may come off as a little odd: “You are about to read a book about the zombie brain. Just think about that for a minute. Let the thought really soak in. Reflect on the decisions you’ve made in your life that led you to this point” (7).

But who am I to say they’re wrong?

The title immediately reveals their frame of reference and sense of humor. After all, puns are an underappreciated art form (and yes, my friends, that is sarcasm). Inside, the chapter headings continue the punny word play: “Gray’s (Undead) Anatomy”, “Tongue-Tied and Twisted”, and “Hungry, Angry, and Stupid Is No Way to Go Through Unlife” all provide a pretty clear picture of their approach to their subject.

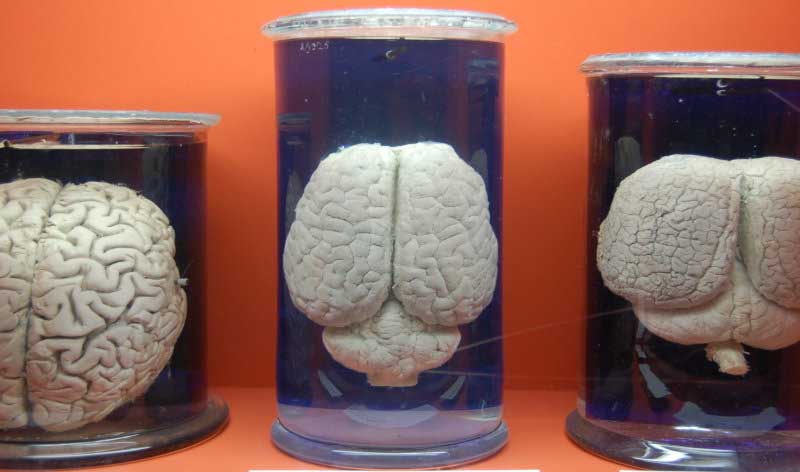

Verstynen and Voytek employ a variety of carefully curated zombie styles to make their many points. George Romero’s classic Night of the Living Dead and its several sequels, Return of the Living Dead, 28 Days Later, Shaun of the Dead, World War Z, Warm Bodies, and a slew of other movies are invoked for easy examples of zombie behavior that illustrate the many possible ways a brain can go wrong. And there are a lot of ways, because, after all, “the brain is a pretty complicated piece of goop” (203). Physical damage, tumors, wiring issues—all can produce a zombified condition even without a wild virus or radiation.

In addition to the Hollywood hit parade, Verstynen and Voytek provide a huge number of real-world references for their proposed methods of action, listed at the end of each chapter. They cite everything from neuroscience and anatomy texts to Nature, The Lancet, and Salon articles to support their positions. If you are so inclined, you can use the accumulated references to give yourself a very nice introduction (and then some) to behavioral neuroscience and its associated psychology.

My only real complaint about the book is that the authors are frequently self-aware and self-referential, and at times downright twee about it: “Obviously, these are complex, unresolved scientific issues well outside the scope of what a couple of goofy, zombie-movie-loving neuroscientists are capable of answering” (100). This quirk only serves to draw attention away from the meat of their information and place it firmly back on themselves. However, the overall tone of the book is playful, and their frequent disclaimers about being zombie-movie-loving neuroscientists can be safely skimmed over without loss of context.

And again, while Verstynen and Voytek provide their readers with a quick, snappy overview of the workings of the brain and related nervous system and endocrine functions, I was left somewhat wanting by their explanations of zombie behavior. As they freely declare, “We’re playing it safe and using a weasel word” (159). There are many traditional undead behaviors to choose from, and while Verstynen and Voytek sort the symptoms into “fast zombie” and “slow zombie”, there are some explanations that feel a little shoe-horned in for form’s sake, and presented without real conviction. Yes, I know I’m being picky about the precision of their proposed zombie brain damage mechanics. But I want to suspend some disbelief, here!

But let’s face it, my complaints are merely quibbles. And quibbles aside, if you are interested in how the brain works, this book will explain it pretty clearly and with great enthusiasm. And if you are writing the Great American Zombie Novel, this book will also provide terrific expository material for you to chew on. Fast zombies, slow zombies, semi-aware zombies—they are all in here, in all their gory glory, with appropriate scientific explanations for their behaviors. Dig in!

E.A. Ruppert contributes book and media reviews for NerdGoblin.com. Thanks for checking this out. To keep up with the latest NerdGoblin developments, please like us on Facebook , follow us on Twitter and Pinterest, and sign up for the NerdGoblin Newsletter.

And as always, please share your thoughts and opinions in the comments section!